So many times I passed this site, these buildings. The Little Mountain Public Housing Project was only blocks from my home, but rarely did I take a close look, as those from the outside were not warmly welcomed. It was sneaky to short cut with your bike through their roads, and local kids did not play in their playground, yet it always was public land. There were no walls but there may as well have been.

Everything changed. Rumours of redevelopment flew around the community. At 62 years the dwellings had lasted long enough. The residents protested – but what of public housing? Their voices unheard, the move was on. I didn’t even know it had started.

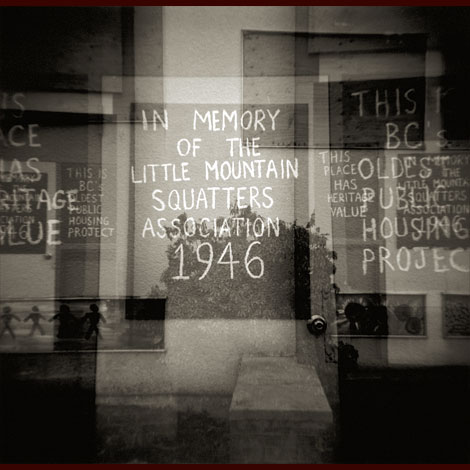

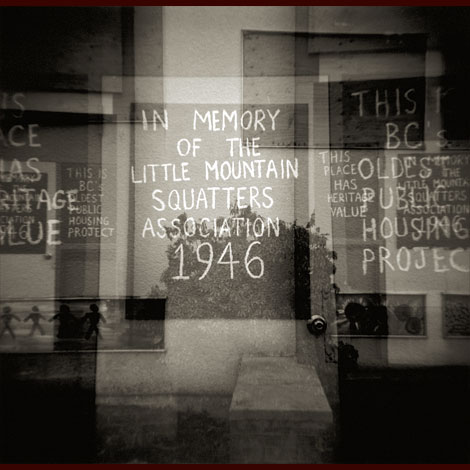

Suddenly one gray December afternoon, plywood covered windows stared back at me from this place I had looked without noticing so many years in a row. Already partly abandoned but not to simply slip away, as the evicted, those remaining, and the community, painted their expressions and recounted history upon the canvas of the tattered buildings. No one moved to remove the pieces.

The stories of the walls intrigued me. I wanted to play a part in this expressive community process, but when would the buildings fall? I felt the pressure of time. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

Mired in the opacity of politics and a climate of secrecy, what emerged over the months to come was a gradual depopulation of the site, and creation of a weird inner urban semi ghost town. The residents shuffled, with no plan evident for the future of the site. The community continued to make their marks.

Hard of Housing became my personal response to the prolonged closure of Little Mountain and the resulting unique community expression.

This site, these buildings, all the people I did not know, could I contribute my perspective, my growing feeling that somehow the messages here must endure? My bag was stuffed with a relatively new to me little black box of plastic, barely passing as a camera, that I had thrown film into but hadn’t yet figured out what purpose I may have for her. Loving her simplicity and spontaneity, she suited my sensibility. Some days I knew there was not enough light for the plastic marvel. My solution was to shoot twice, sometimes 3 even 4 times, the resulting photographs as layered as the unfolding story of Little Mountain.

Prowling the buildings, I regarded the ever growing cracks and the thickening grime. I read the words placed so carefully in the plywood covered windows, the graphic array representing both those accomplished with a brush and those for whom this was pure expression. All was compelling and the voices of history spoke.

I knelt, sat, and lay in the sweet spring grass, trying to grasp the possibilities for greater perspective. Daisies popped, and remnant gardens too, untended and left to their wild independence. I started to love this place, there was a suspended peace amongst the vacated buildings. The walls continued to talk. I remained free to play and see deeper into this fragile, sticky and complicated pie. The little plastic piece of nothing seemed to have a definite something going on.

The site was ever changing. Not just the seasons, new words, new graphics, and things moved around. Iron railings disappeared, opening new views to explore. These were subtleties, but I knew this place and I noticed. The voices became less hopeful as time passed. The end appeared to be in sight, the messages increasingly desperate.

Metal posts appeared around the periphery, and soon my access to this place of solitude and retrospection was barred. This had been my space to play the graphic, the organic and the structural upon each other and connect the threads of this canvas for one last time into something more than what was obvious at a glance. It was not only about the site, the buildings, which really were nothing. It was of the people who lived here and moved on, and those who now have made their expressions, and even of myself.

The fences up, I could only work from beyond the gate. The walls felt so far away, I could no longer crawl into their textures. I incorporated the infuriating fence as much as possible, it was part of the viewpoint, a final wall separating one side from the other. I also brought a step stool, hoping to sometimes see beyond the wall for a clear view. I promised the growing army of security guards that I had no desire to go over the wall as others had.

All corners secured, the buildings tumbled in the late fall and into the early winter, upon a soft bed of leaves that had fallen just before. The wooden structures were no match for the metal jaws that consumed the buildings bite by bite. One building and a small handful of tenants remained, in the midst of 15 acres of barren rubble.

It was hard to watch as the component elements that were Little Mountain became slivered, ripped and finally destroyed. Little Mountain consumed and challenged me, and was now gone. It was now my turn to take my plastic marvel and move on.

When I first started photographing in the abandoned Little Mountain Public Housing project, I approached it with a straight photographic documentary point of view. That approach soon proved to be insufficient to express the displacement, the loneliness and the despair of those uprooted, and those who remain in this semi-ghost town in the middle of a major Canadian city.

I started bringing all of my current photographic experiments into the public housing project, and the sight of me and my often weird gear brought me into contact with the building caretakers, the public utility guys, the security guards and some of the remaining habitants. While my practice is not to photograph people, all of these contacts have proven invaluable in shaping my understanding and subsequent imaging of this vanishing neighborhood. The building caretakers have kept me up to date on the latest and greatest guerrilla public art going up as giant panels around the site, the public utility guys usually have tidbits of information on the future, the security guards are mostly pests, and the local habitants are able to explain the meanings in the guerrilla public art.

My collection of photographs now include straight photography, slit-scan photography made with a modified Holga camera, pinhole photography made with my homemade Drãnoflex camera, and extra-long exposure large format photography enabled with my proprietary homebrew chemistry.

I’ve always got fresh experiments brewing, and by visiting Little Mountain and making pictures, I hope to witness rebirth.

For more information on my techniques, click here for our Techniques page.

Google Analytics